by Tate Englund

For those who have practiced with me over the years, you know that my style has evolved. So has my personal practice. I no longer teach or practice the same way I used to. I think this is the natural evolution of yoga and, really, of life. We learn, we grow, we adapt, we change.

A question I often get in my trainings and workshops is, “What poses do you no longer teach or practice?” It’s a good question that I hadn’t really thought about until I was asked. It was almost like these poses just fell out of the rotation.

But there really are reasons. It’s not “just because I don’t like Warrior 1” …which I don’t, by the way. So, I thought I’d share my insight on why I no longer practice certain poses or actions.

Here are 5 poses/actions I no longer teach or practice:

Let me start off by saying I don’t think any of these poses are bad or wrong. I just look at the risk vs. reward, and if I don’t see the reward as worth the risk, I cut it out. Dunzo. I still practice some handstand and forearm variations that I would consider not safe, but the feeling I get when I do them outweighs the risk (like tearing my rotator cuff… which I did doing something I still practice 😉).

Keep in mind, I taught all of this stuff for years.

1. FULL SPLITS (Hanuman)

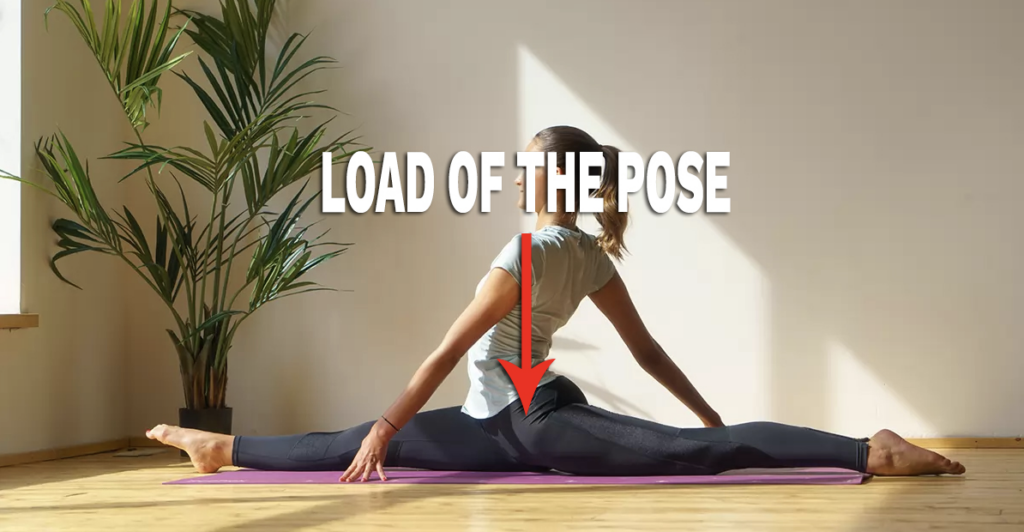

If full splits are done well, where you’re using strength to get into the pose, strength while you’re in the pose, and strength as you exit, it’s a totally fine pose IMO. But I know how most people are. Nobody does this. They “hang out” in splits. There isn’t activation of the hamstrings and hip flexors the entire time. Why? Because it’s f’ing hard. Nobody wants to do that. It’s horrible.

So why are splits potentially problematic? When the hip flexors and hamstrings aren’t active, which is the case for 99% of people, the downward force has to go somewhere. When you’re hanging out in splits, you’re hanging out in your hip joints. When the load is in the joints with no muscle engagement, it can lead to instability, wear and tear, and potential degeneration of the joint. Not something I want to have happen to my hips, or anyone else’s.

Now, don’t get me wrong, having flexible hamstrings and hip flexors is a great thing to have. I just work on that in other postures that I feel are safer and, more importantly, allow for a better ability to strengthen while in the lengthened position. So I stay in half splits and work on anjaneyasana and low lunge quad stretches where I can do a better job of turning the muscles on as I stretch.

2. HEADSTAND (Sirsasana)

This also includes tripod headstand. It comes down to 2 things for me.

- Your cervical spine is not designed to handle the weight of your body

- The fear factor for headstand isn’t the same as handstand or forearm balance, which means more people try headstand before they have any business trying headstand.

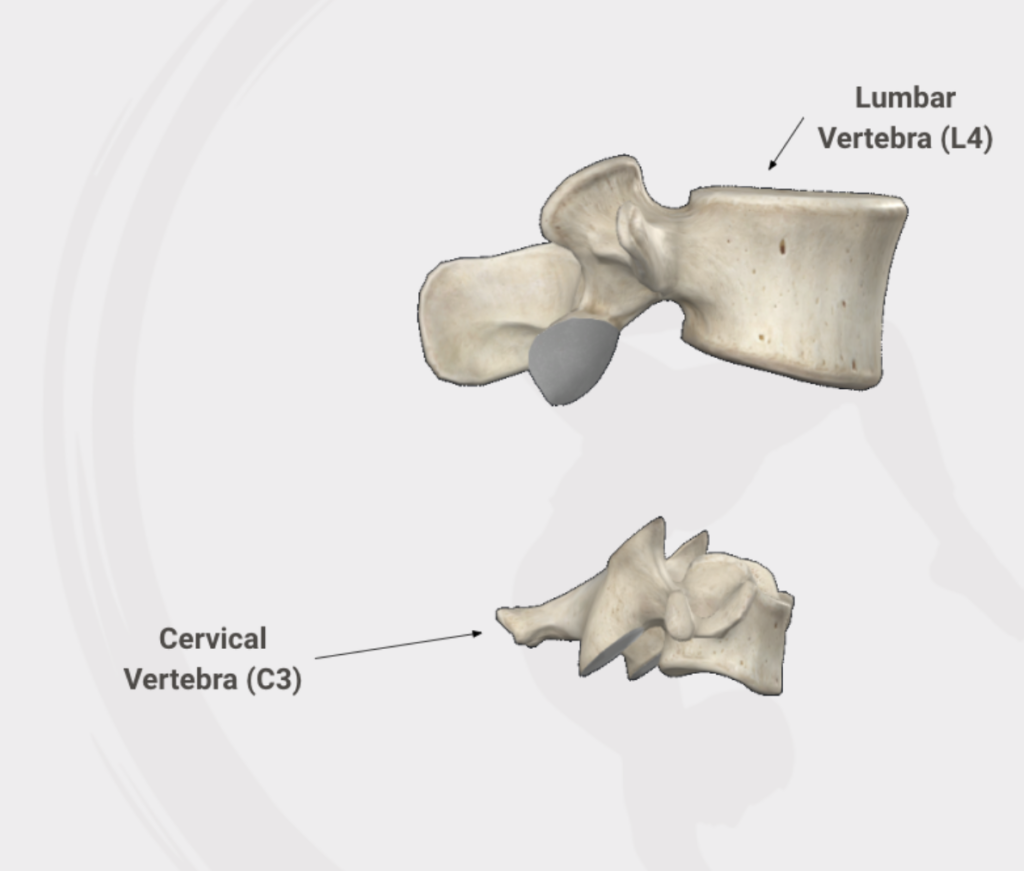

When you look at the sheer size of the lumbar vertebral body compared to the cervical spine, you can see that the lumbar spine is meant to handle load; the cervical spine is not—it’s meant to be more mobile.

When headstand is done properly, there really is no weight on the head. The problem is, most people don’t have the strength, knowledge, and proper setup. Headstand should basically be a forearm balance with your hair touching the floor. It shouldn’t be balancing or “standing on your head.”

In a public class, I can’t ensure that Steve in the back corner isn’t going to kick up with all the pressure on his head. The fear factor for Steve isn’t the same as for other inversions. Fear of injury, falling, etc., keeps many students from ever attempting handstands or forearm balances, but the same student would have no problem kicking into a headstand. That’s the main reason I no longer teach it. If I’m being honest, the fear factor should be reversed. People shouldn’t be as scared of handstands or forearm balances, and more people should think twice about headstands.

If someone is dead set on being able to do a headstand, I always recommend getting proficient in handstands and forearm balances first. That way, they have the proper shoulder strength, control, and proprioception to do a headstand correctly. I know that will take much longer, but your neck will thank you for it. If they don’t have the patience, I’ll suggest private sessions so we can ensure proper safety and setup.

3. TRADITIONAL HALF PIGEON POSE

Two big reasons I no longer teach this:

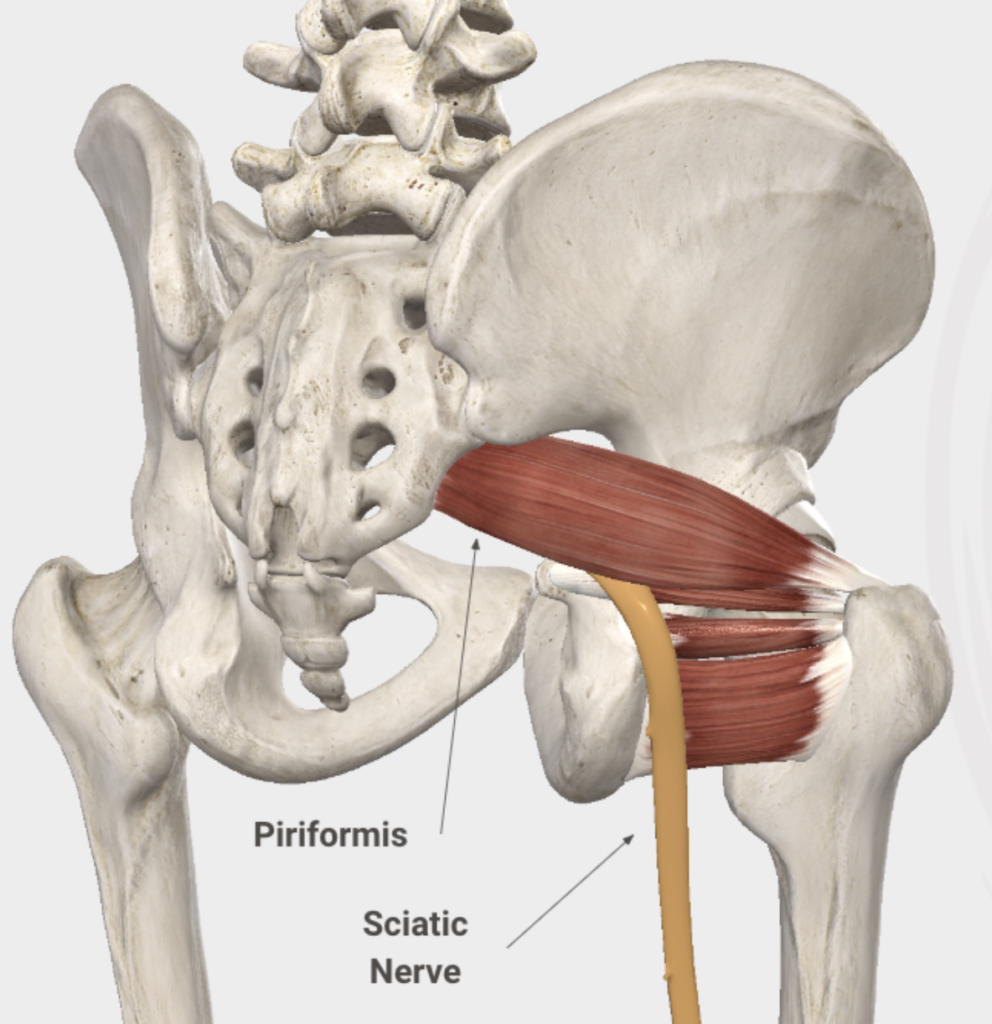

- Modern bodies tend to have weak butt muscles and weak outer hip muscles. This means that a small muscle that’s supposed to be a helper, the piriformis, has to take on way too much. Yoga often over-taxes this muscle, both loading and stretching it. If irritated, it’s a literal pain in the butt. To make things even more interesting, you have a huge nerve called the sciatic nerve that runs under, over, or even through the piriformis. If the piriformis is irritated, it can press on or squeeze the sciatic nerve, causing pain, tingling, and/or burning sensations that can go all the way to the toes. Fun stuff!

- Because the thigh bone and the shin bone are on separate planes and angles, pigeon pose can put excess force on the knee, causing pain on the outside or inside of the knee.

So what do I teach instead? The 90/90 pigeon. This option takes the pressure off the piriformis, puts the thigh bone and shin bone on the same level, so there’s no chance of excess force on the knee. It also gets you more into the outer part of the hip, which tends to be tight for most people. And as a bonus, you have great access to strengthening the muscles at the same time. So, it’s a win-win-win.

4. ANY FOOT/LEG BEHIND THE HEAD STUFF

Do I really even need to say anything? Why? Why do we need this range of motion? Sorry, but outside the bedroom, if that’s your thing, why would we ever need or want our foot behind our head? We don’t walk down the street thinking, “You know what would make this walk better? Putting my foot behind my head.”

Okay, I’ll be serious now. It’s 100% passive range of motion. You can’t use your hip muscles to pull your leg behind you. You either need to use your arms to crank the leg back or have a teacher assist you. I’m just cringing thinking about a teacher pulling a leg behind someone. I lose sleep over these kinds of things.

There’s no need whatsoever for this kind of range of motion, and the potential for something to go wrong, either in the pose or later in life, is just not worth it.

5. FULL BINDS

What do full binds do well? They help with internal rotation, which is a big plus for the shoulder joint. It is so important to have good internal rotation in our shoulders.

Ok, so why don’t I teach them?

- They’re usually practiced 100% passively. No strength in the stretch. When the hands clasp, the shoulder muscles instinctively shut off. Why is this a problem? The more mobile the joint, the more the body sacrifices stability. Where there is more mobility, there is a greater chance of instability. Our shoulders are a ball-and-socket joint, just like the hips, but our hips are like a ball in a bowl of bone, while our shoulders are more like a ball sitting on a tea saucer. The shoulder is mainly stabilized by soft tissue, which means there’s more need for strength in those tissues to stabilize the joint. It’s really important that we have mobile shoulders, which means a balance of strength and flexibility.

- Most students have to contort their torso or hips to get into the full bind, which takes them out of the integrity of the pose. Don’t believe me? Watch your students, or your own body when you’re in a full bind in side angle. Most are no longer in side angle; they’re in some weird humbled warrior, bind thing. It becomes more of a forward fold than anything.

- And honestly, I just don’t think they feel that good for most people.

So, how do I replace the great internal rotation benefit that comes with binding? Sleeper stretch and other non-traditional yoga variations, half binds, or full binds where I make fists and push together without grasping or clasping hands. This way, the muscles of the shoulder pull into position but have to hold rather than shutting off. If you still want to practice full binds, to add strength, think about holding the bind with the hands but with the upper arms, try to break the bind.

Remember, it’s not about the pose itself. It’s about risk vs. reward. Think about why we are practicing these poses. If you feel the reward outweighs the risk, go for it. It’s about eliminating blind-faith following—the “just because” or “because my teacher says so” mindset that happens a lot in Western yoga.

As always, I ask that you question everything.

Let me know whether you agree, disagree, or see things differently.

-Tate